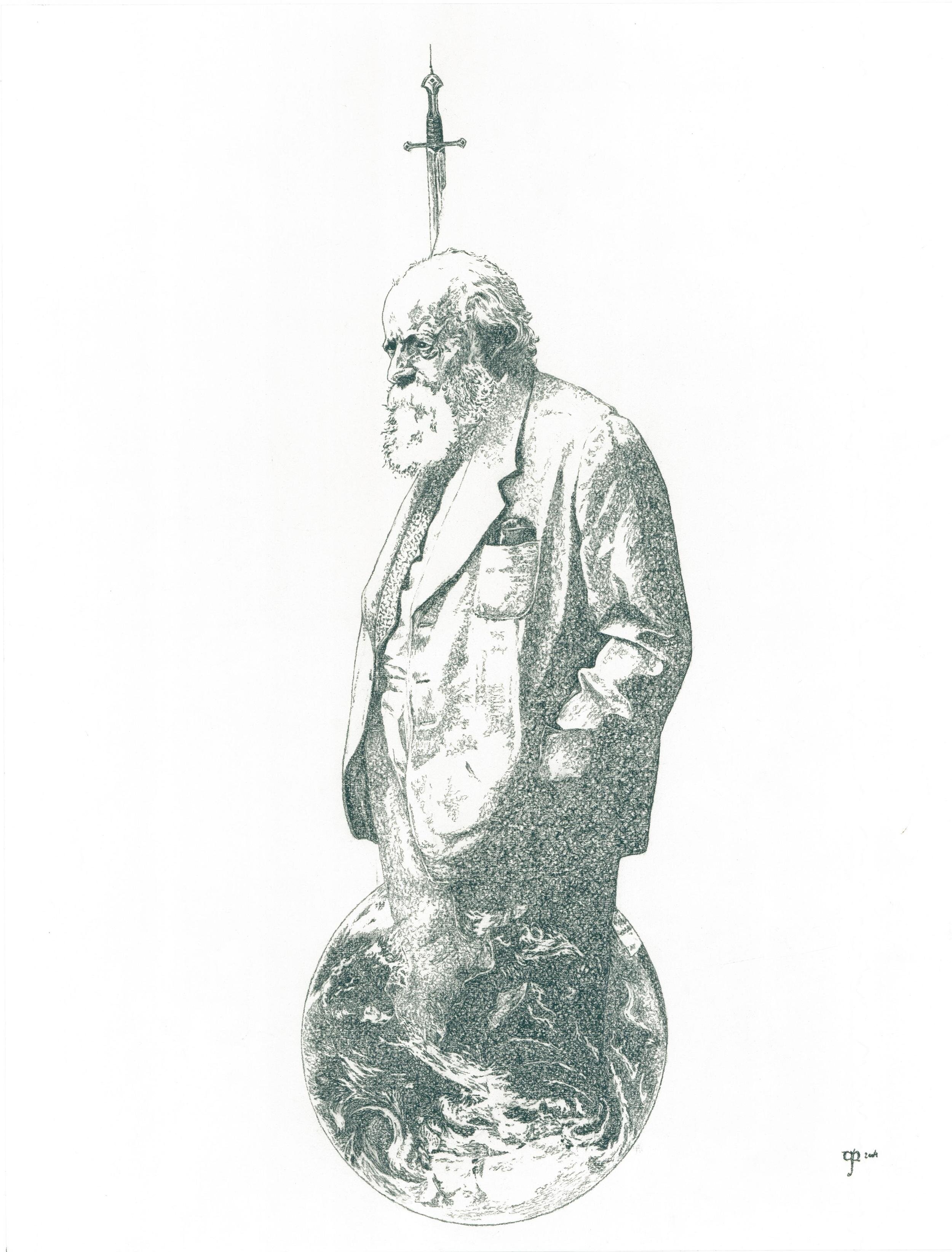

Oil on Mexican wood bowl (2012).

In Mexico, it is common to see different Catholic saints painted in rough-hewn, elongated wood bowls used for making bread, called bateas, or ‘boats.’ I wanted to continue this tradition, painting in a folk-style appropriate to the medium; but instead of limiting myself to Catholic ‘saints,’ I wished to paint important ‘exemplars’ from different religious traditions.

Here I wished to depict the complex religious identity of Black Elk, whose great vision saw the coming together of all the sacred hoops, and who, in his own life, preserved and maintained the sacred traditions of his people, while at the same time, working with—in perhaps complex and difficult ways—his new Christian environment, according to his own understanding of his vision.

Oil on Mexican wood bowl (2010)

In Mexico, it is common to see different Catholic saints painted in rough-hewn, elongated wood bowls used for making bread, called bateas, or ‘boats.’ I wanted to continue this tradition, painting in a folk-style appropriate to the medium; but instead of limiting myself to Catholic ‘saints,’ I wished to paint important ‘exemplars’ from different religious traditions.

The first I painted was ‘Thomas of the Desert,’ Thomas Merton, the Christian Trappist monk, social critic, and author of the bestselling autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. Although Merton is beloved for many different reasons, I most admire Merton the contemplative, the explorer of the inner landscape, who put together the classic, Wisdom of the Desert. Thus, I painted him on a desert hilltop with a hoe in one hand and a pen in the other, showing his calling to the hermetic life, his calling as a writer, and the work of the hands to which every Trappist monk must commit. He is encircled in a furrow he has dug with the hoe, which is meant to represent the Zen enso, ‘circle,’ symbolic of ‘enlightenment’ and ‘emptiness.’ (Merton was also a student of Zen and Japanese brush calligraphy.) Above him is the Christian tau cross, which might also signify T for ‘Thomas.’

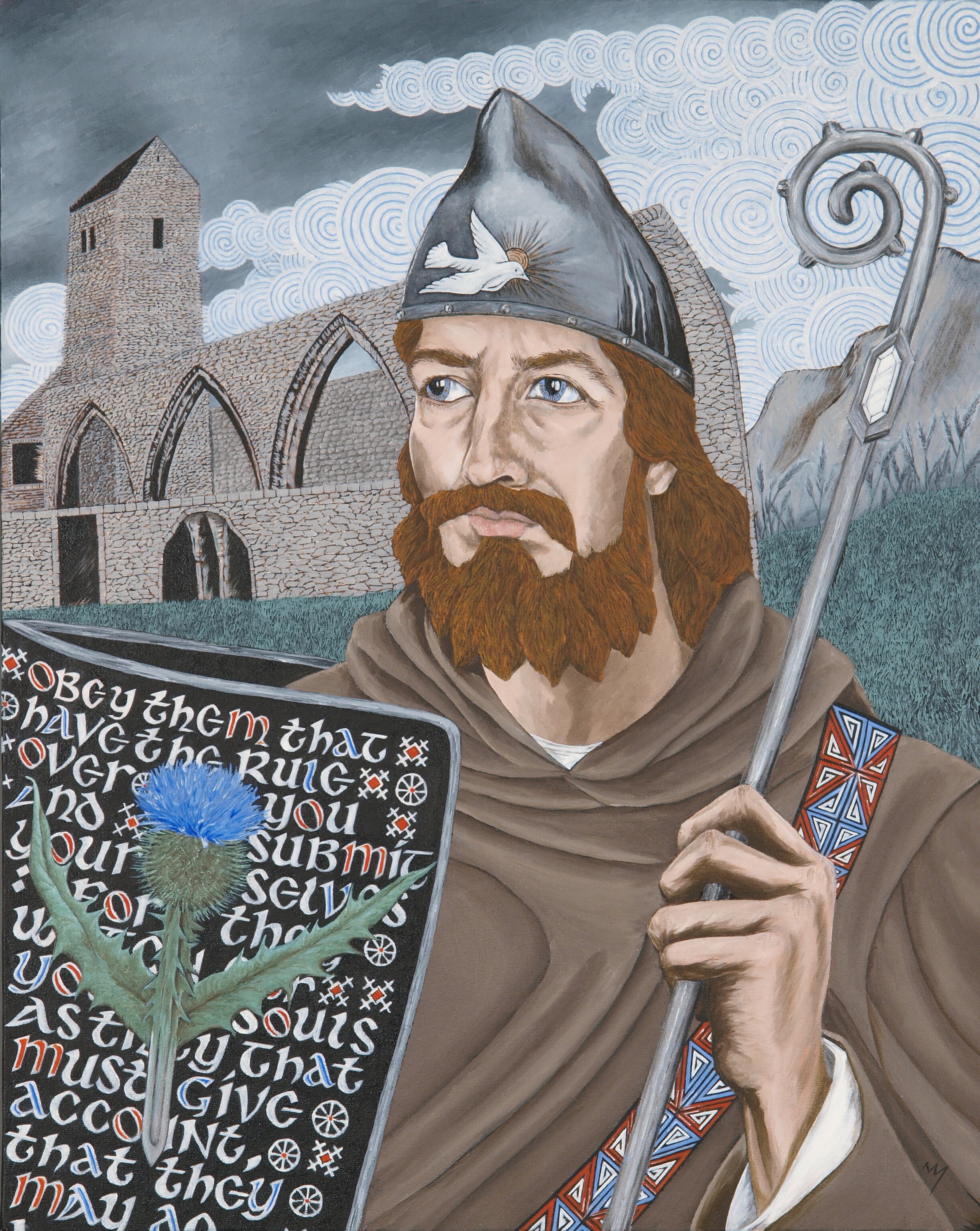

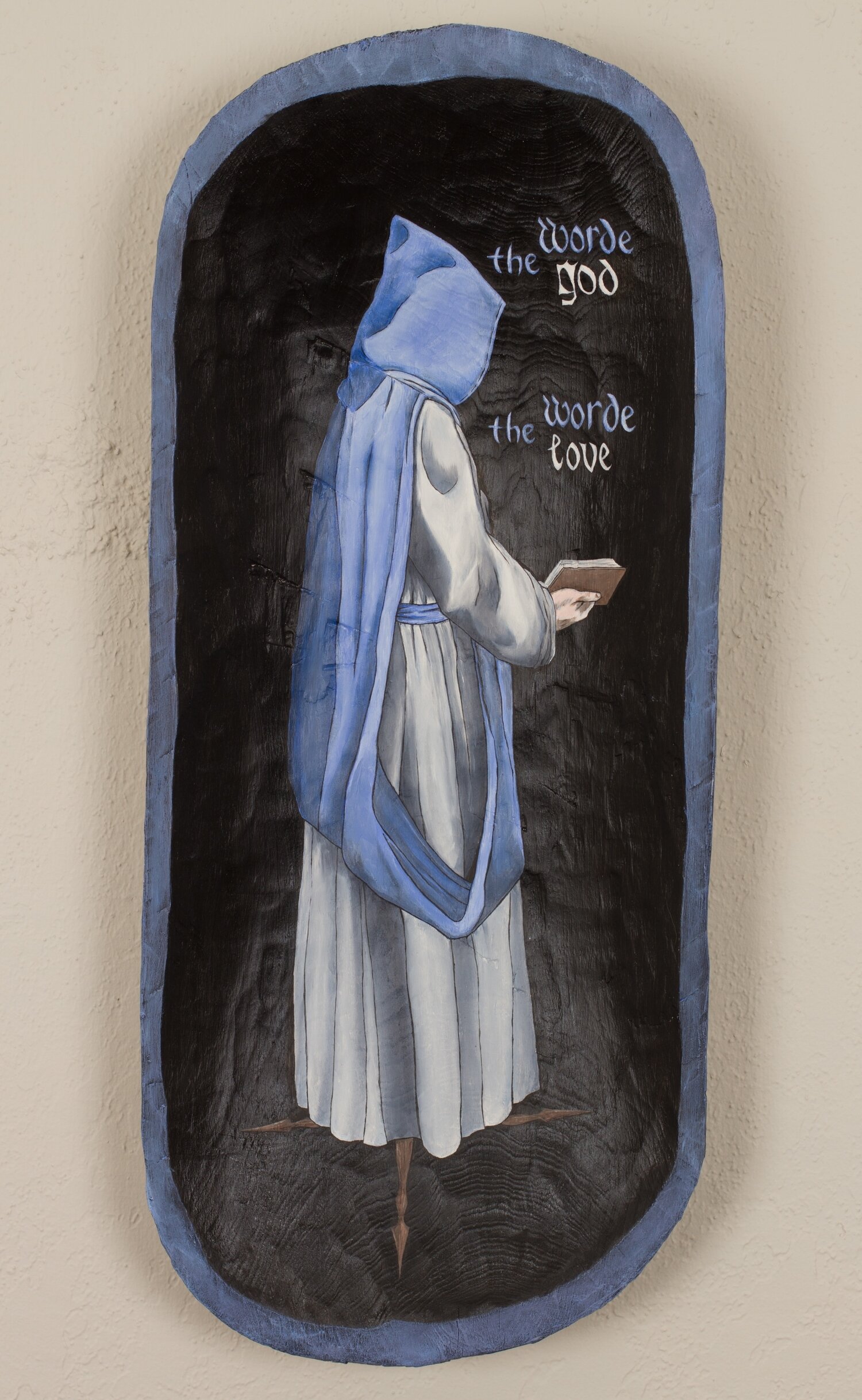

Oil on Mexican wood bowl (2012).

Ten years after the bloody Spanish conquest of Mexico, in 1531, an Aztec convert to Christianity, named Juan Diego, was climbing up a hill long associated with the Aztec mother goddess, Tonantzin. As he climbed, he heard someone call his name and looked up to see the most beautiful young woman he had ever seen, hovering in the sky, a “woman clothed with the sun” and standing on the moon. She told him that she was the “Mother who Loved All,” and said, “All who sincerely ask my help in their work and in their sorrows will know my Mother’s Heart.” Then she sent him to tell the Spanish bishop about her appearance; but the bishop only dismissed him as an ignorant peasant. Then she sent him back again, and this time the bishop asked for some proof of her appearance. So she had Juan Diego collect all the wildflowers he could find on the hill in his tilma, his cloak made of cactus fiber, and she arranged the flowers in the tilma and sent him to the bishop once again with this ‘sign.’ When Juan Diego opened his cloak, the wildflowers were all gone and Castilian roses from Spain fell from it on the floor, and on the cloak itself was an image of the Mother of All, just as Juan Diego had seen her in the sky. Then everyone believed him and a church honoring the Our Lady of Guadalupe was built on the ruins of the Temple of Tonantzin at the place of the appearance.

To the Spanish Catholics, she seemed to be an appearance of Mary, the Mother of God, in the form of the Black Madonna that was in the monastery of Guadalupe in Spain—a sign that she and her blessings had followed them across the ocean to this new land. To the Aztec people, she seemed a sign that Tonantzin, the mother goddess, was still with them, even if she now dressed in the strange new clothing of the Spanish. Because she appeared to Juan Diego as a meztiza, a ‘mixed one,’ being morena, dark haired and having some of the coloring of the native people, but with European features, she became the symbol of a long process of healing for a land that had been bathed in the blood of European conquest. She became the Patroness of Mexico, the mother of the meztizos, the symbol of a new people who would soon be neither European nor Indigenous, but a mixture. For although there were would continue to be pockets of isolated cultures in Mexico, the future of the land and the people would be determined by their mixing, and by their wrestling with the competing and conflicting desires of their dual heritage.

This is Our Lady of Guadalupe as I conceive of her. She is described as a beautiful 16-year-old young woman wearing a blue mantle covered in stars. I have more clearly emphasized the mixture of Baroque European and Indigenous folk styles of artwork and symbols, and have also made her traditional association with the famous agave plant (from which tequila is made) much more explicit.

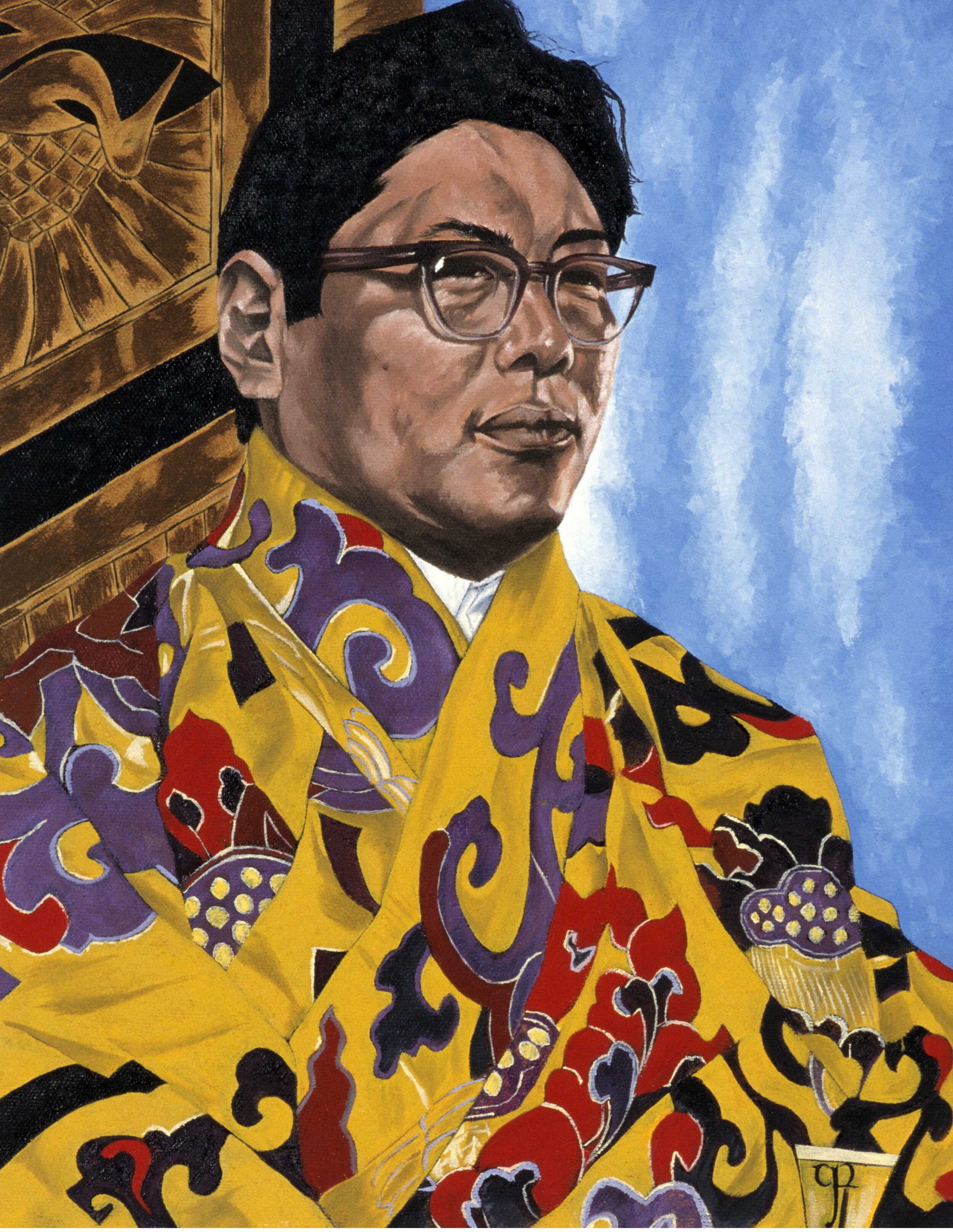

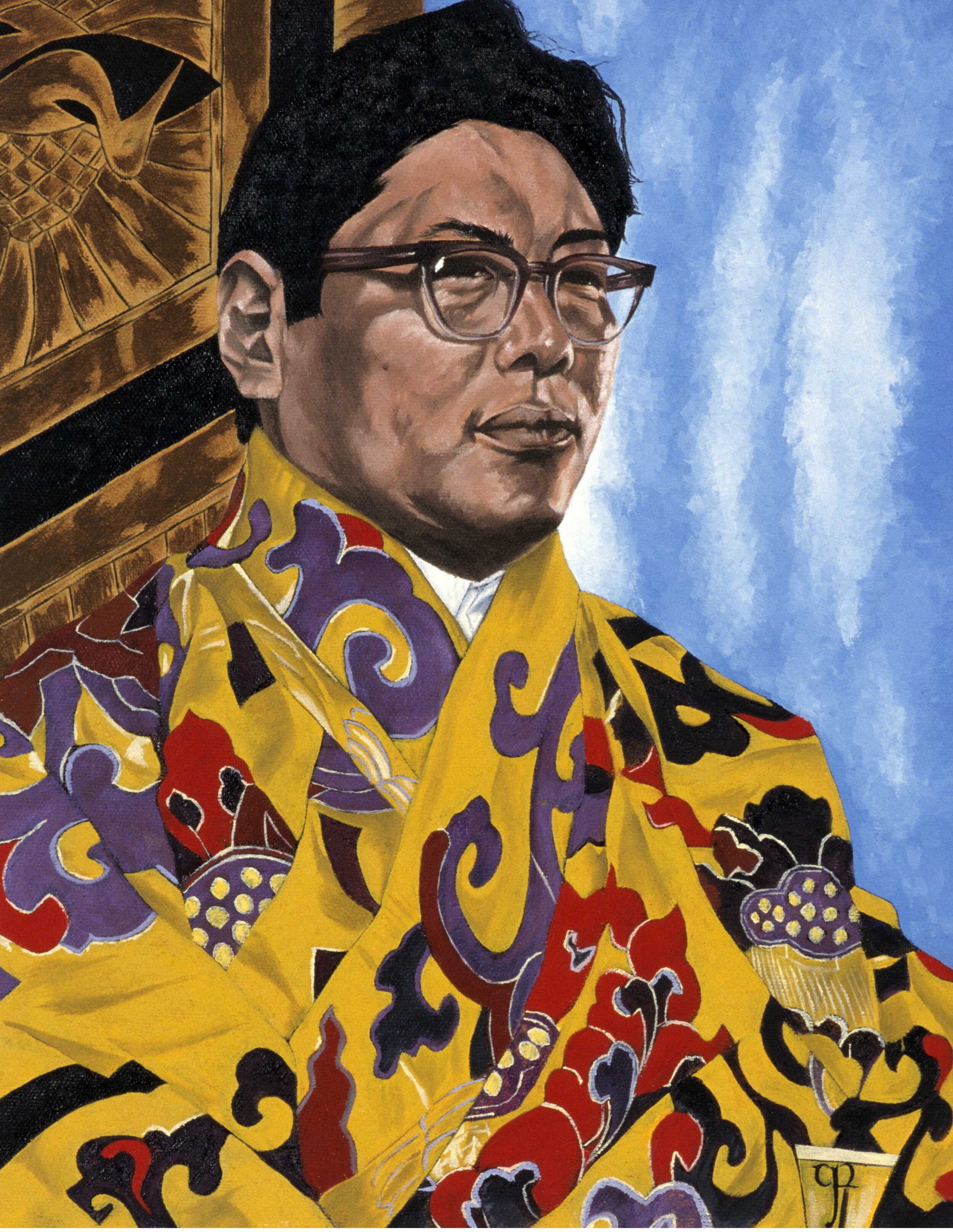

Oil on canvas (2019). Trungpa is depicted here in the Chuba of Shechen Kongtrul.

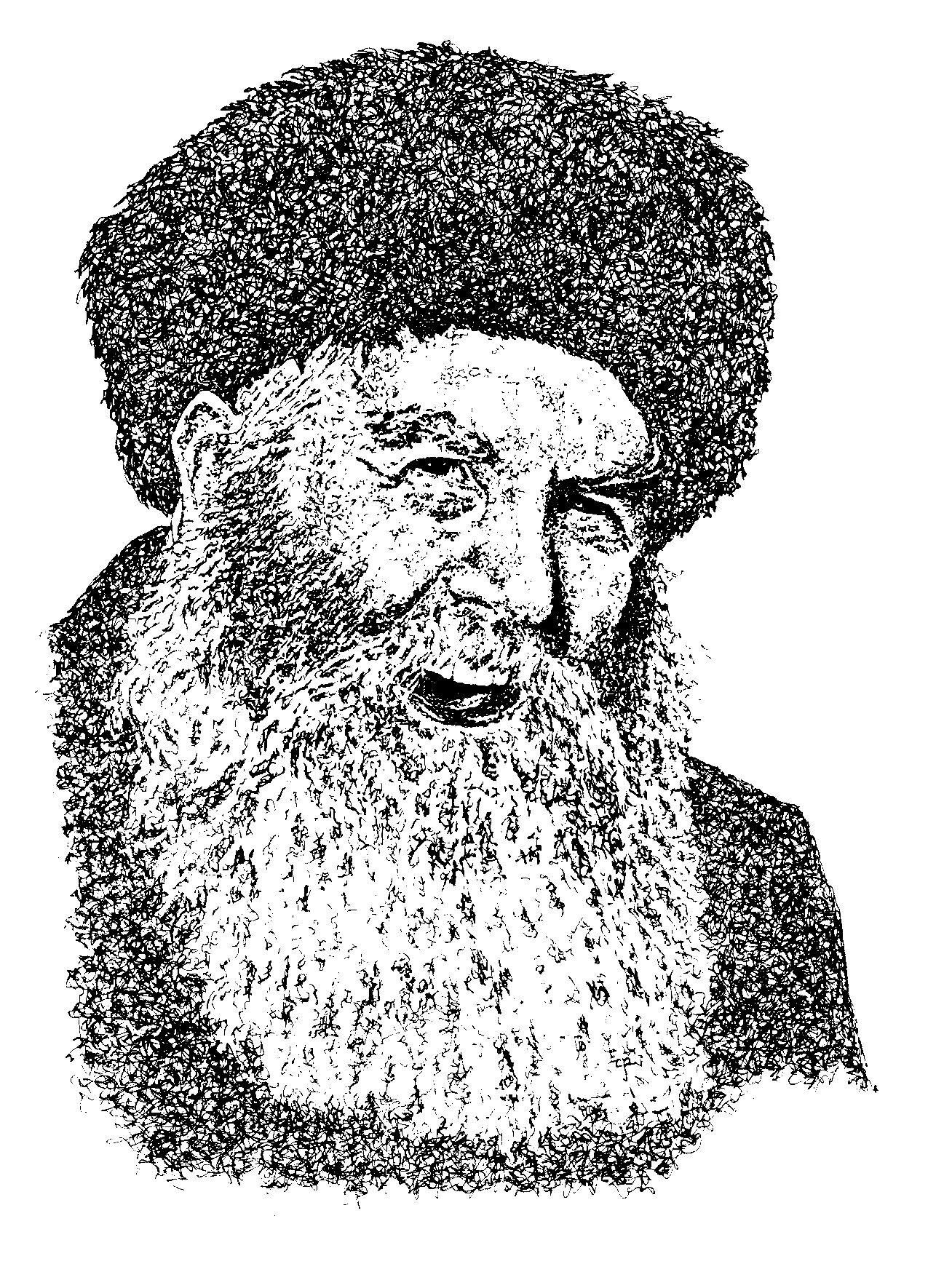

Oil on Mexican wood bowl (2013).

Hasidic master Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak Schneerson (1880-1950) was the sixth rebbe of the Habad-Lubavitch lineage of Hasidism.

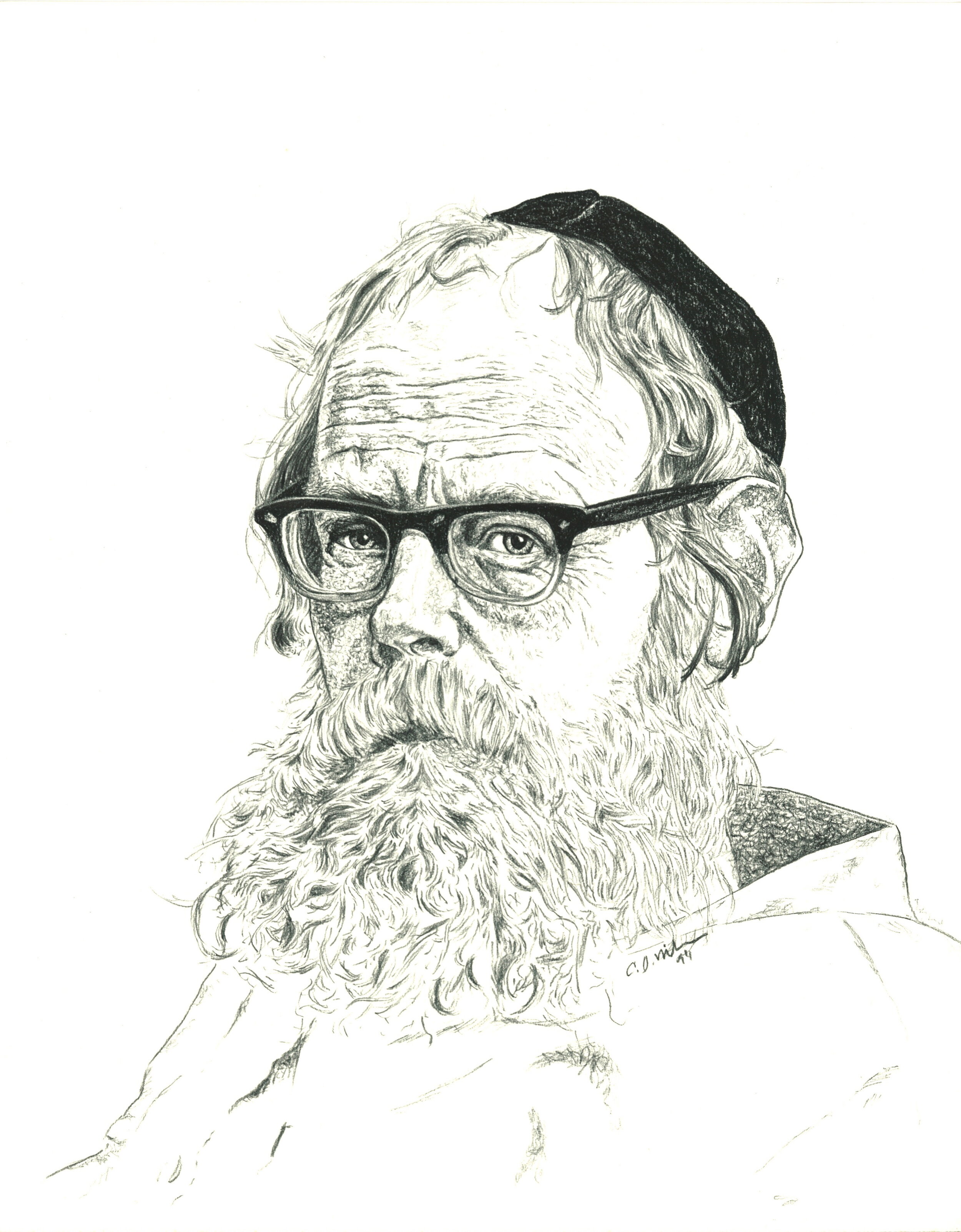

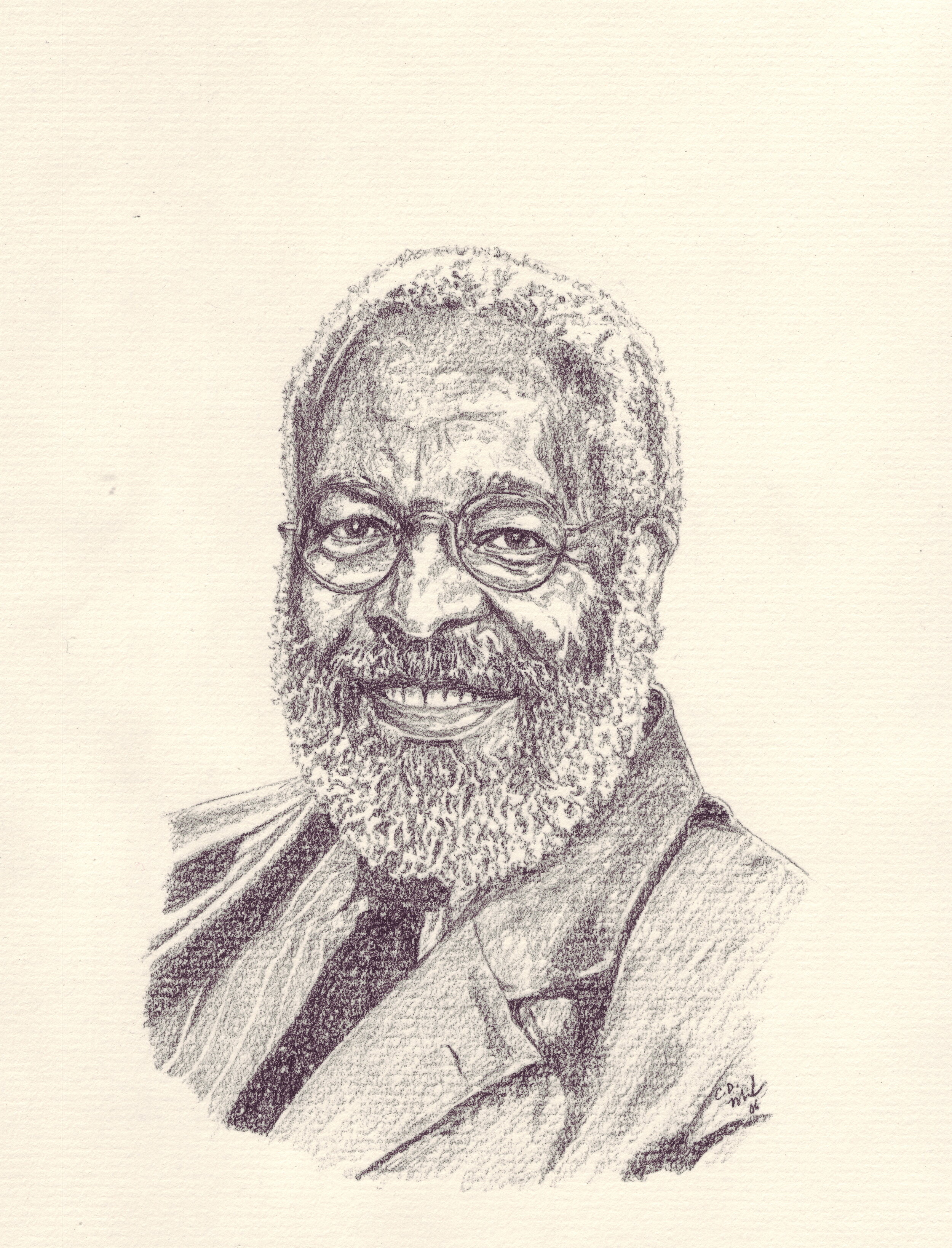

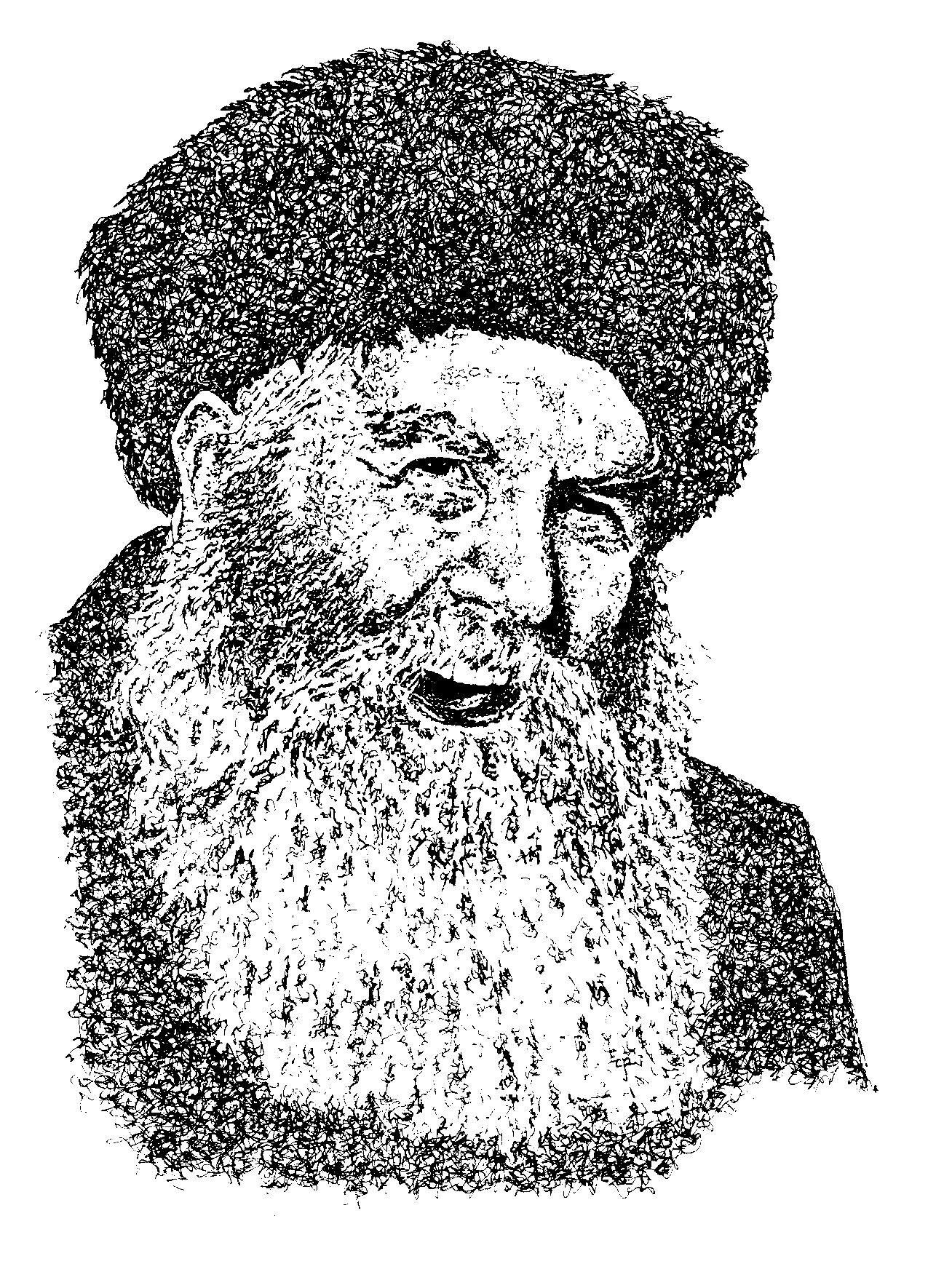

Charcoal on paper (2005).

Hasidic master, Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak Schneerson (1880-1950) was the sixth rebbe of the Habad-Lubavitch lineage of Hasidism.

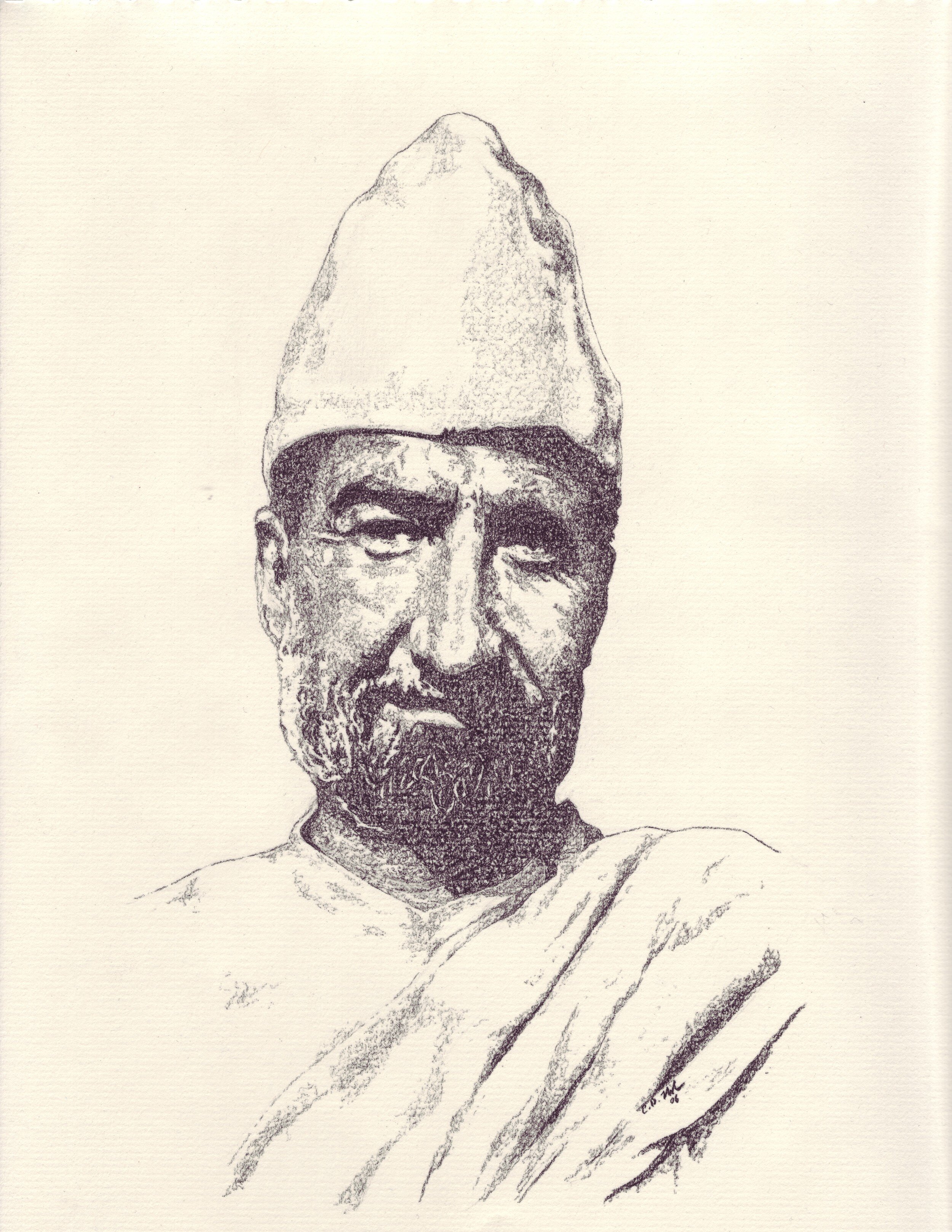

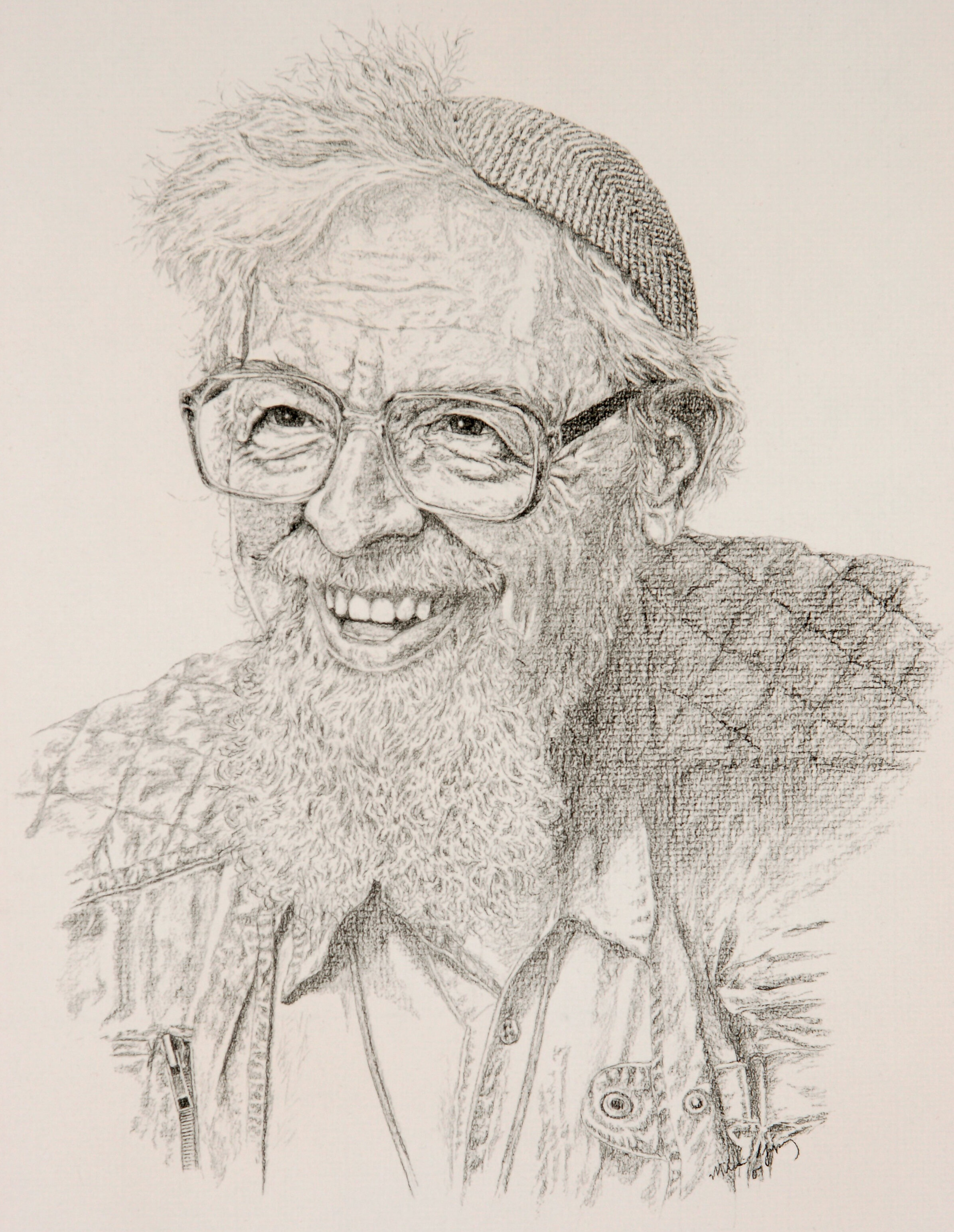

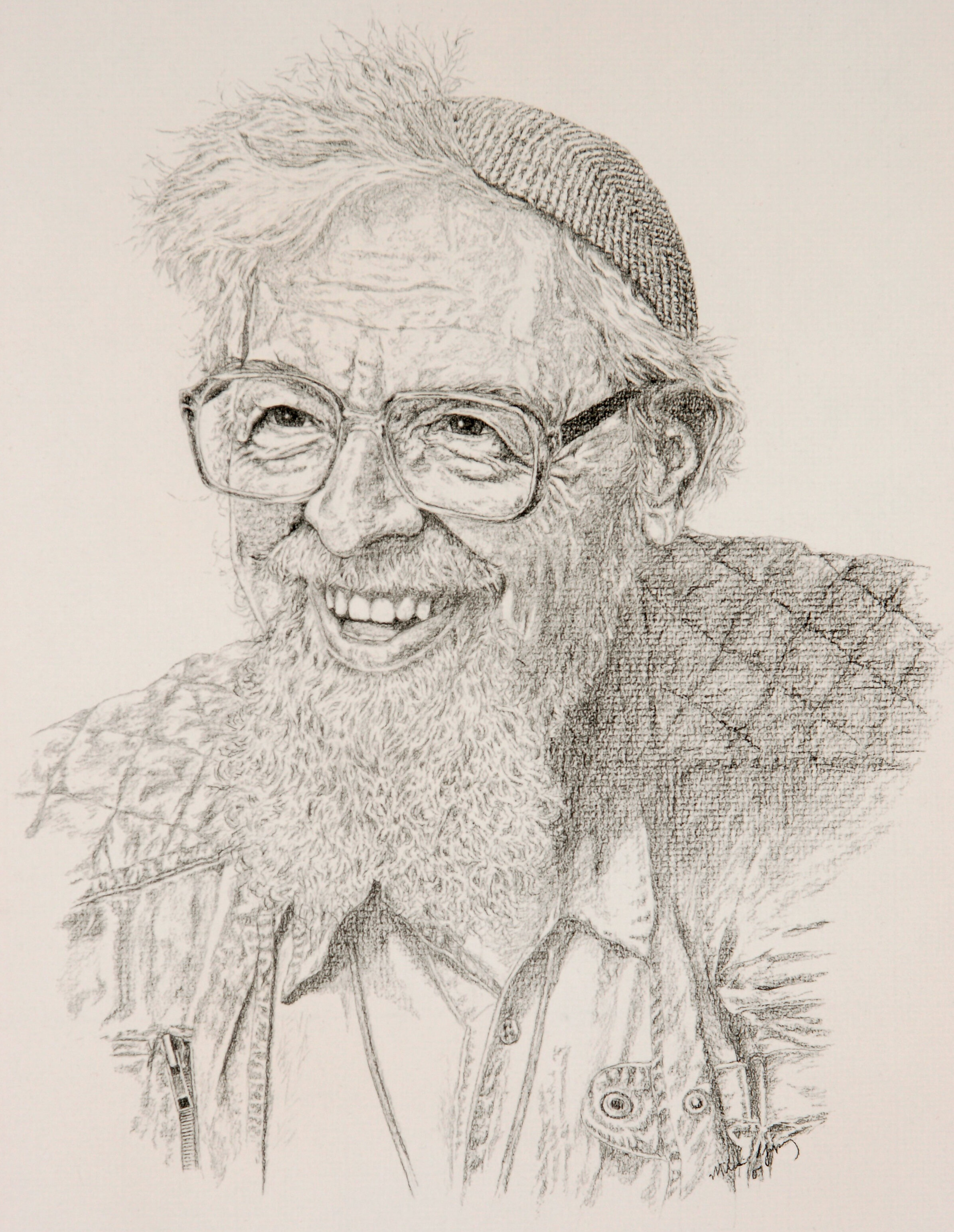

Charcoal on paper (2007).

Zalman Schachter was born on August 17th, 1924 in Zholkiew, Poland to Shlomo and Hayyah Gittel Schachter. In 1925, his family moved to Vienna, Austria where he spent most of his childhood. His father, a Belzer hasid with liberal tendencies, had him educated in both a "leftist" Zionist high school, where he learned Latin and Modern Hebrew, and a traditional Orthodox yeshiva, where he studied Torah and Talmud.

In 1938, when he was just 13, his family began the long flight from Nazi oppression through Belgium, France, North Africa, and the Caribbean, until they finally landed in New York City in 1941.

While still in Belgium, Schachter became acquainted with and began to frequent a circle of HaBaD Hasidim who cut and polished diamonds in Antwerp. This association eventually led to his becoming a HaBaD hasid of the Lubavich branch, in whose yeshiva he enrolled after his family arrived in New York. He received his rabbinic ordination from the Central Lubavitch Yeshiva in 1947.

Within a few years of his ordination, he began to travel to college campuses with his friend Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, at the direction of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and took up a post as a congregational rabbi in Fall River, Massachusetts. Later, he would also serve as a congregational rabbi in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

By 1956 he had acquired a Master of Arts degree in the Psychology of Religion (pastoral counseling) from Boston University and taken up a teaching post in the Department of Religion at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada, which he would hold until 1975. Soon after, he was instrumental in the founding of the Department and Clinic of Pastoral Psychology at United College (later University of Winnipeg).

By 1968, Schachter had earned his Doctor of Hebrew Letters from Hebrew Union College and had become separated from the Lubavitcher organization over issues relating his controversial engagement with modern culture and other religions, but he continued on as an "independent hasid," teaching the experiential dimensions of Hasidism as one of the world's great spiritual traditions. That year, he was also influential among the group who formed Havurat Shalom in Somerville, MA.

The following year, inspired by Havurat Shalom, Christian Trappist spirituality and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Schachter founded the B'nai Or Religious Fellowship (now ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal) with a small circle of students.

He ordained his first rabbi, Rabbi Daniel Siegel (one of the current leaders of ALEPH) and helped to found the Aquarian Minyan of Berkley, California in 1974.

A few years earlier, he had begun to study Sufism and meet with Sufis in California. This eventually led to his being initiated as a Sheikh by Pir Vilayat Khan in the Sufi Order of Hazrat Inayat Khan in 1975. That year he also became professor of Jewish Mysticism and Psychology of Religion at Temple University where he stayed until his early retirement in 1987, when he was named professor emeritus.

In 1980, he and two others, ordained one of the early influential women rabbis, Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb (now based in New Mexico).

1985 saw the birth of a new period in his life. That year Schachter (now Schachter-Shalomi) took a forty-day retreat at Lama Foundation in New Mexico and emerged with a new teaching that became the foundation of his book, From Age-ing to Sage-ing, and the catalyst for the Spiritual Eldering movement.

In 1995 he accepted the World Wisdom Chair at the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) and found a home from which he could teach contemplative Judaism and ecumenical spirituality in an accredited academic setting.

In 2004, Schachter retired from Naropa University. That year, he also co-founded the Sufi-Hasidic, Inayati-Maimuni order with Netanel Miles-Yepez, thus combining the Jewish Hasidic tradition with Islamic Sufi tradition into which he had been initiated in 1975.

He died on July 3rd, 2014 and is buried in Green Mountain Cemetery in Boulder, Colorado.